Methane emissions show 'concerning' spike in Covid-19 pandemic's wake - Kayrros

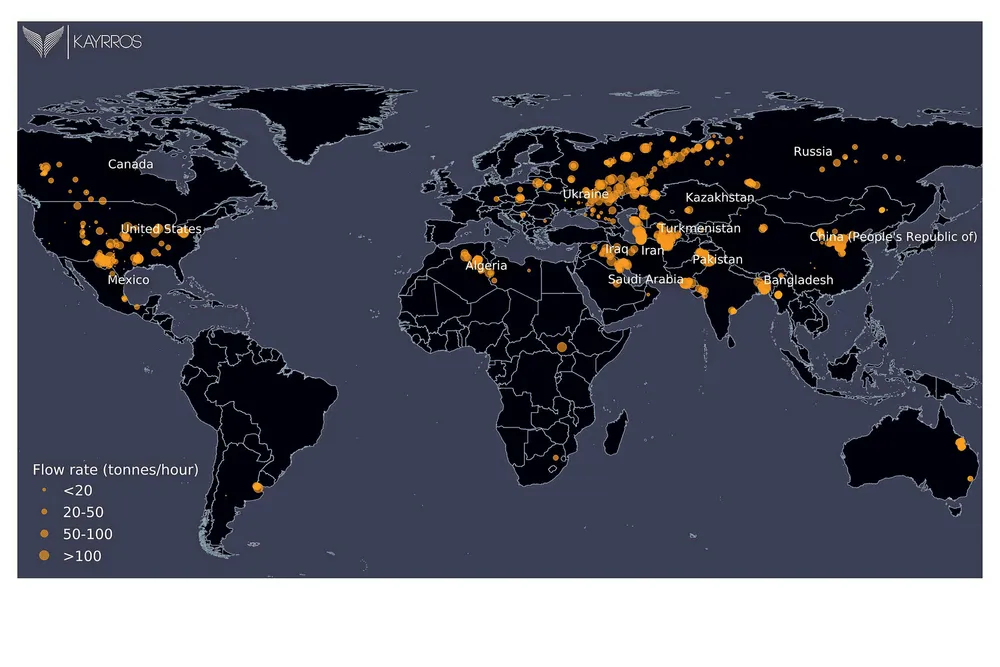

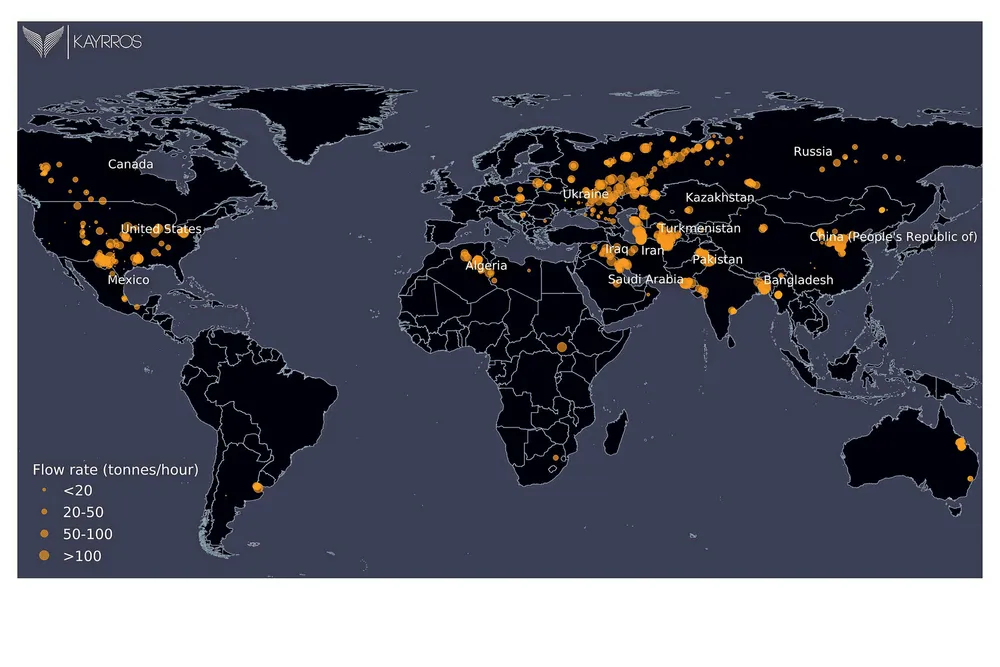

Methane tracker says satellite data show steep increase as cost cuts and weak gas prices hit operational practices

Methane tracker says satellite data show steep increase as cost cuts and weak gas prices hit operational practices