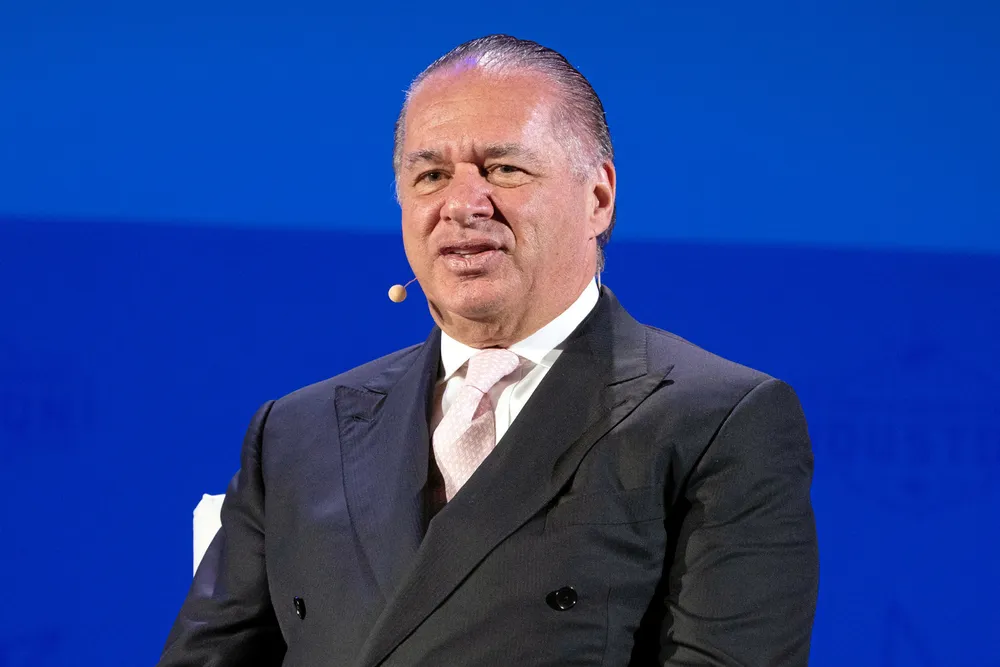

LNG pioneer Charif Souki still searching for ultimate success

Visionary leader was fired from Cheniere and faces new struggles at Tellurian

Charif Souki is widely regarded as one of the pioneers of the booming US liquefied natural gas export industry.

He built Cheniere Energy from the ground up and positioned it to be one of the nation’s largest LNG exporters. He then moved on to co-found Tellurian Energy, which has a similar goal but is yet to turn this new dream into reality.

Souki, now 69, was born in Egypt and moved to Lebanon before emigrating to the US.

He graduated from Colgate University in New York state, then spent time as a banker on Wall Street and as a restaurant magnate.

A natural entrepreneur, Souki owned the Mezzaluna restaurant in Los Angeles in the mid-1990s. This eatery was famous in its own right, but gained notoriety as the location that Nicole Brown Simpson dined on the evening before her infamous murder.

Sickened by the media circus surrounding the prosecution and trial of Nicole Brown Simpson’s killer, her husband American footballer OJ Simpson, Souki decided to sell the restaurant and try the energy industry.

Souki has frequently said he had no idea what fracking even was before he started Cheniere in 1996.

The company first planned to make its money producing oil and gas in the deep-water US Gulf of Mexico but unsuccessfully.

Souki hit on the idea of importing LNG to the US at the turn of the century when there was a projected severe shortage of natural gas in the US but the shale revolution turned everything on its head.

Cutting the ribbon

When Souki cut the ribbon at his Sabine Pass regasification facility in Louisiana in 2007, it was already obsolete.

Hydraulic fracturing and horizontal drilling in places such as the Barnett and Marcellus shales was not only eliminating the need for gas imports, it was positioning the US to become a gas exporter.

Without skipping a beat, Souki called back many of the same people who had funded his import facility and said he wanted to rebuild it into an LNG export facility. The price tag: Approximately $20 billion.

Souki’s original vision may have been flawed, but his recognition of the changing fortunes of US gas production put Cheniere ahead of the curve.

By 2013, the company’s stock was soaring and Souki was the highest-paid chief executive in the US, taking in $142 million that year.

But Cheniere was still two years away from exporting its first cargo of LNG, and problems were on the horizon.

Souki had already obtained the green light for a second LNG export facility at Corpus Christi, Texas, and was interested in building a third, near Lake Charles, Louisiana.

He wanted to expand into other areas, including having Cheniere produce its own gas for export and reinvesting the capital for this from the company’s revenues.

This drew the ire of activist investor Carl Icahn, who had purchased a 15% stake in Cheniere and wanted stronger shareholder returns instead of additional rapid growth.

Icahn convinced the members of Cheniere’s board of directors to fire Souki in 2015, a couple of months before the company he called “my baby” began exporting LNG.

Showdown

Instead of taking his money and returning to Aspen, Colorado, Souki decided he would seek a showdown and start another LNG export company, Tellurian.

By 2016, Souki had tapped into his considerable group of friends and funding sources to get the company off the ground.

His plan was to produce and sell his own natural gas and export it from an LNG terminal built essentially in the same location he had planned for Cheniere’s third facility near Lake Charles.

“[The plan] is what got me fired at Cheniere, but I was right,” Souki said at CERAWeek presented by S&P Global in March this year.

Tellurian has acquired a significant gas production operation in the Haynesville shale of Louisiana, but the primary goal — building Driftwood LNG — has become increasingly elusive.

Even though company executives late last year and - again - earlier this year said they had plenty of banks interested in funding the project, Tellurian had to put out a $1 billion bond offering in late August.

After investor insurrection, it was pulled in mid-September and the company’s stock nosedived as two of the three 10-year contracts Tellurian had on the books were terminated.

Souki, who had sold his dreams of a company producing its own gas and exporting it, with an air of inevitability found Tellurian didn’t have the $12 billion needed to proceed with Driftwood.

He said in a message in late September that the company would look for “strategic equity investors", then followed it up with a second statement admitting to “mistakes” in the company’s initial plans for Driftwood.

For now, Souki said Tellurian would remain a natural gas producer, with Driftwood’s completion left on the back burner.

It remains to be seen whether the decision to pull back from risk during the current debt market turmoil will prove to be a canny move.

“In terms of our current business, which is very solid, and our future business, which is the Holy Grail, [the question is] how much risk we’re willing to accept in order to continue to stay on schedule, and frankly, given the turmoil in the debt market, that risk is no longer worth it,” he said.

(Copyright)