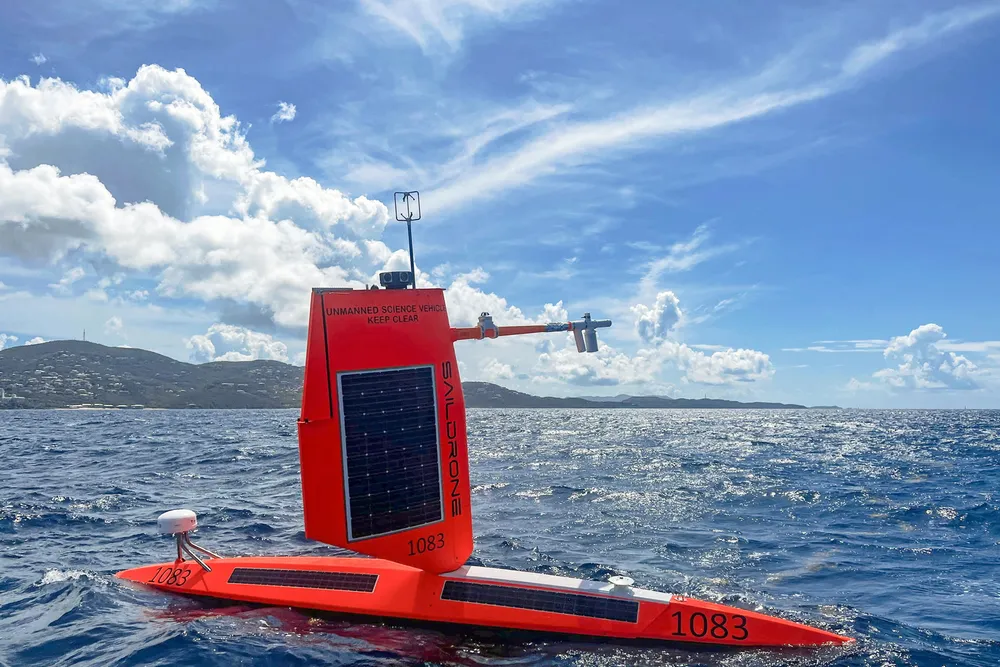

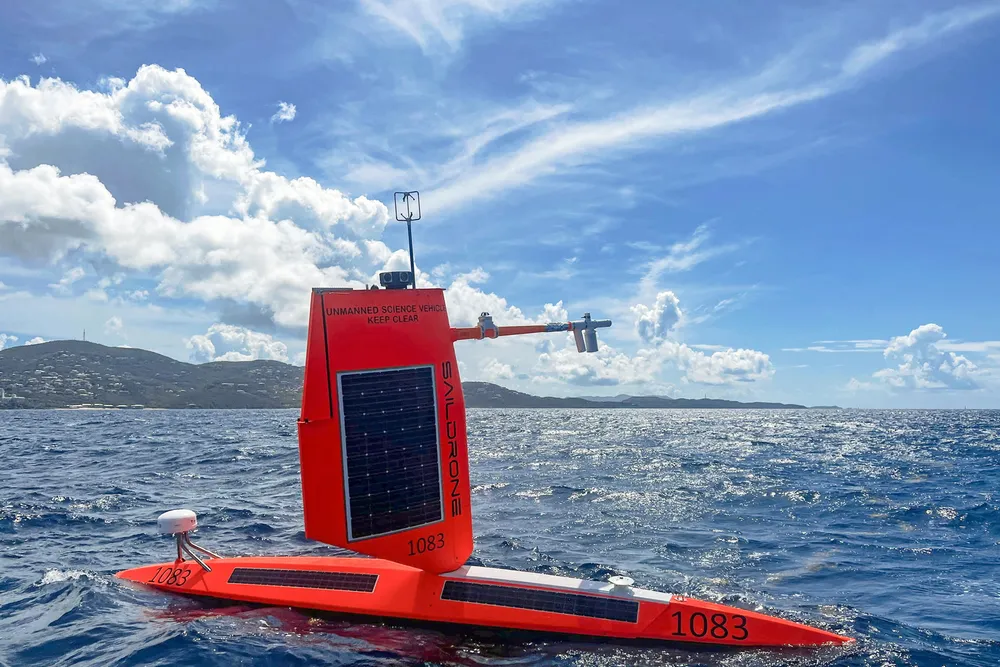

Intrepid drones set off for Atlantic’s hurricane alley

Uncrewed vehicles gather valuable data for storm forecasting, while NOAA issues a revised 2022 outlook

Uncrewed vehicles gather valuable data for storm forecasting, while NOAA issues a revised 2022 outlook