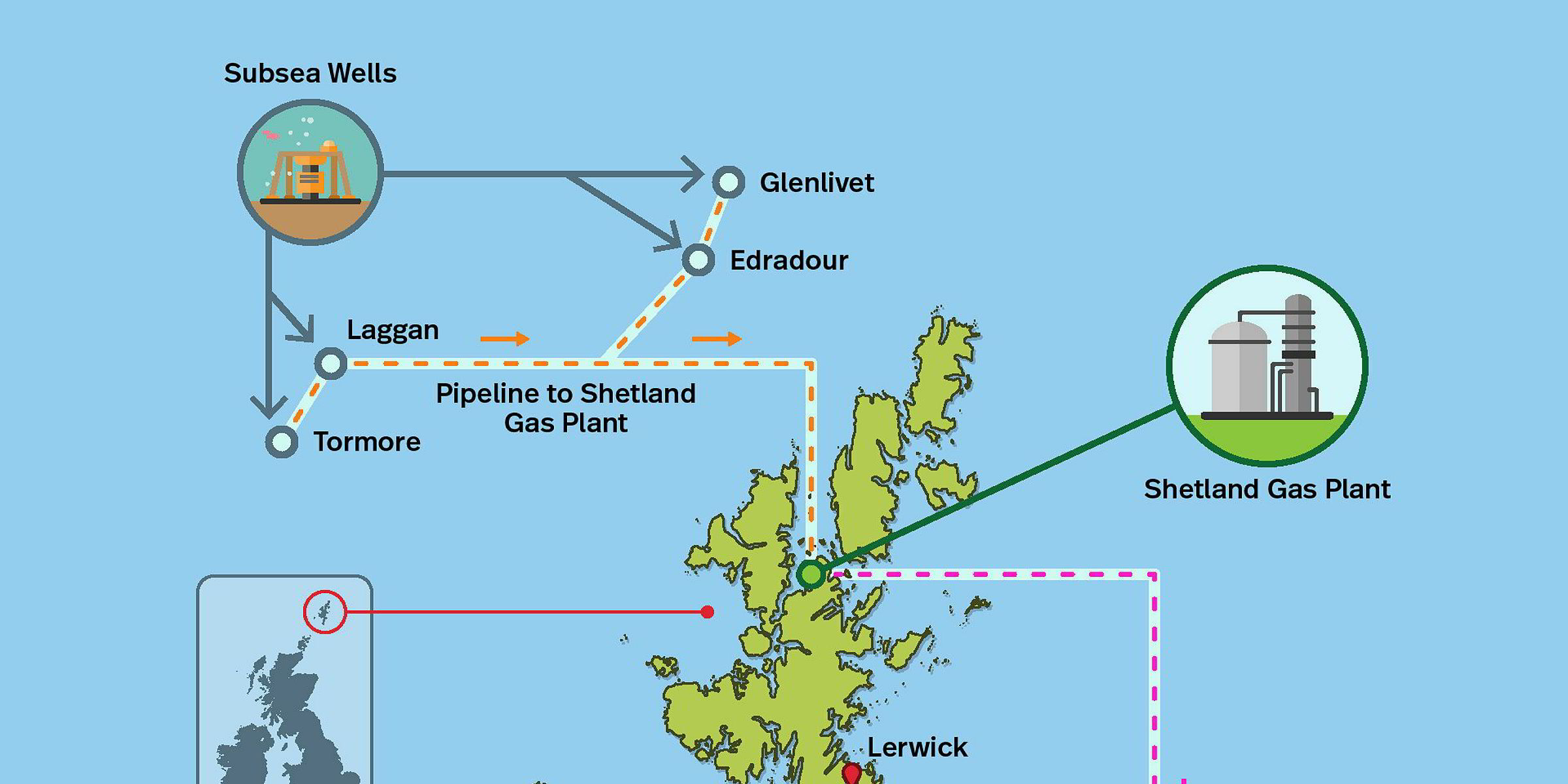

Late this summer, Total turned on the taps at the Edradour and Glenlivet gas and condensate fields, just 18 months after announcing first production at the nearby Laggan-Tormore development.

The 35-kilometre subsea tie-back will bring an additional 56,000 barrels of oil equivalent per day to the Laggan-Tormore production system, which includes a 143-kilometre pipeline and onshore gas processing plant.

The Edradour and Glenlivet development comprises three subsea wells in water depths of 300 to 435 metres.

Total says the project was completed at 30% under the initial budget, a savings partially attributable to a series of events that allowed the development team to accelerate the schedule.

“When the project was sanctioned in 2014, the original plan was to start up Edradour at the end of the third quarter of 2017 and Glenlivet the following year, in the fourth quarter of 2018,” says Kevin Boyne, West of Shetland asset director for Total E&P.

The subsea industry will have to be innovative from now on to remain competitive.

Kevin Boyne, Total E&P

Giving priority to the vessels doing installation and development work, Total planned to conduct final drilling and completion activities with North Atlantic Drilling’s semi-submersible West Phoenix over two summers in 2017 and 2018.

“The early project works and drilling works went very well, so that by the end of 2016 we were re-evaluating the project and thought there was an opportunity, if we mobilised the rig early in the (2017) season, to potentially complete the two Glenlivet wells prior to carrying out the final project tie-ins at Glenlivet, and to work on Edradour preferentially in the early part of the season with the project vessels,” Boyne says.

“We decided it was worth an attempt,” he says. “At the worst, we thought we may not finish both Glenlivet wells and would have to carry one over into 2018.”

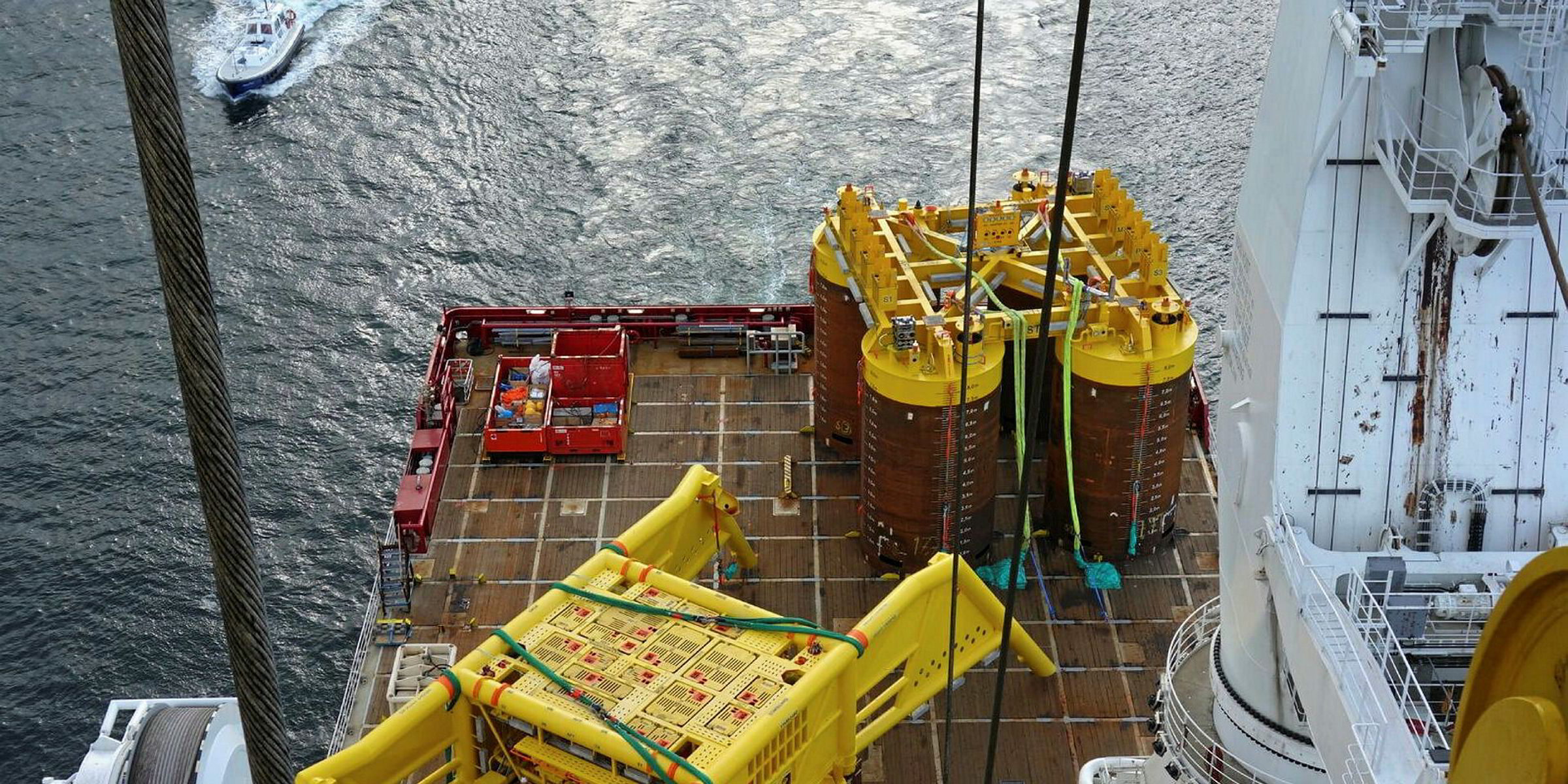

Total mobilised the rig in March, early in the season, with the goal of finishing by the end of June. The agenda included a stretch in May and June when the rig would be working alongside the project development fleet — “com-ops”, or combined operations, “which have to be very carefully planned”, he says.

“As it happened, the drilling operations went very well, as they had in 2016,” Boyne says. The drilling team finished a month early, in May, paving the way for early start-up of both Edradour and Glenlivet.

Familiarity on both sides — the drilling contractor and the field partners — helped smooth the process. Total knew the systems on the rig, and the drilling team was familiar with Total’s subsea technology, having worked on Laggan-Tormore.

As the end of the summer season approached, Total began final commissioning of the two fields, completing the activities required for start-up, such as dewatering the flowlines and filling the systems with monoethylene glycol (MEG), and saving non-critical activities such as rock-dumping for later.

“That meant we were able to accelerate by a further couple of months and start both fields in August, instead of at the end of October,” he says.

The accelerated schedule helped Total shave 30% off the original budget for Edradour and Glenlivet, but it was not the sole factor, Boyne says.

“We came in under budget, and the key to that, first, was standardisation,” he says. “We used the same type of subsea equipment as Laggan-Tormore. We were able to get derogations to use equipment that we had acquired years earlier, and we retained people on both the project and the drilling sides.”

The market downturn played no insignificant role. Many contracts were signed in 2014, Boyne says, before the oil price tanked. The prolonged downturn allowed Total to renegotiate some contracts with equipment suppliers and with the drilling contractor, which gradually reduced the West Phoenix day rate from more than $400,000 per day in 2014 to about $145,000 per day this summer.

Good planning helped the operator avoid downtime.

“Because we focussed so much on the summer seasons and very careful project execution planning — detailed planning between project start-up and drilling activities — we were able to avoid any major issues,” Boyne says. “We had contingency plans but we didn’t have to use them.”

The project included at least one technology first for Total — the deployment of seam welded tubes on the Glenlivet umbilical, an innovation that the company says produces a lighter, stronger umbilical that is less costly to fabricate.

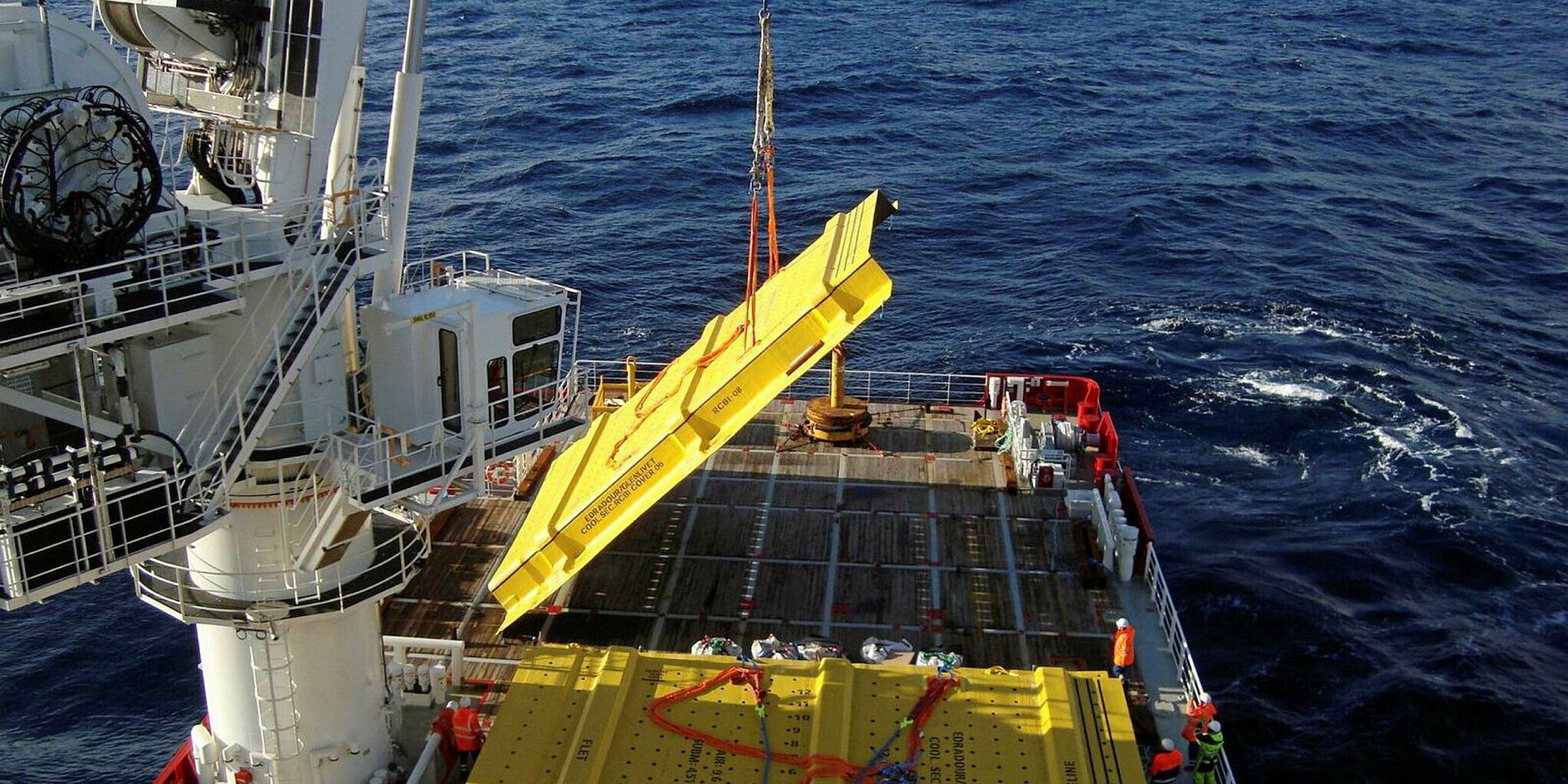

To reduce the risk of corrosion in the Edradour production flowline, pipeline engineers designed a 1200-metre section of the pipeline coated with thermally sprayed aluminium to enhance cooling.

The cooling section is protected by ventilated glass reinforced plastic covers, a “novel” technology that Total has said enhances its “understanding of the thermal performance of rock-dumped pipelines”.

Such innovations are critical if subsea developments are to remain viable in a low oil price environment, especially in high-cost areas such as the North Sea, Boyne says.

Opportunities to take advantage of a down market are temporary, but the emphasis on co-operation and standardisation that the downturn has produced could be longer lasting.

“Deep water itself is potentially at stake unless costs can be driven down,” he says. A market recovery will not necessarily change that, he insists. Subsea will still have to compete with other energy sources, including shale gas, shallow-water production and renewables.

“Subsea must be competitive in the energy market,” he says. “Innovation initiatives have been launched in the past and maybe not fully led to fruition. There is still risk of that.

"But I think the global environment has changed to such an extent that the subsea industry will have to be innovative from now on to remain competitive with other oil and gas projects and to compete on the overall global energy market.”

A specifically North Sea challenge is to find cost-effective ways to produce small, remote discoveries, including many in Total’s UK portfolio.

“We have a few small discoveries around, either our acreage or others’. But they’re very small, so it’s challenging,” Boyne says. “We have a big exploration portfolio West of Shetland, around Laggan-Tormore, but also around Corona Ridge and farther north.

“We’re looking at all the exploration possibilities very intensively.”

Total E&P UK operates Laggan-Tormore, Glenlivet and Edradour with a 60% interest alongside partners Ineos Oil & Gas and SSE E&P, with 20% interest each.