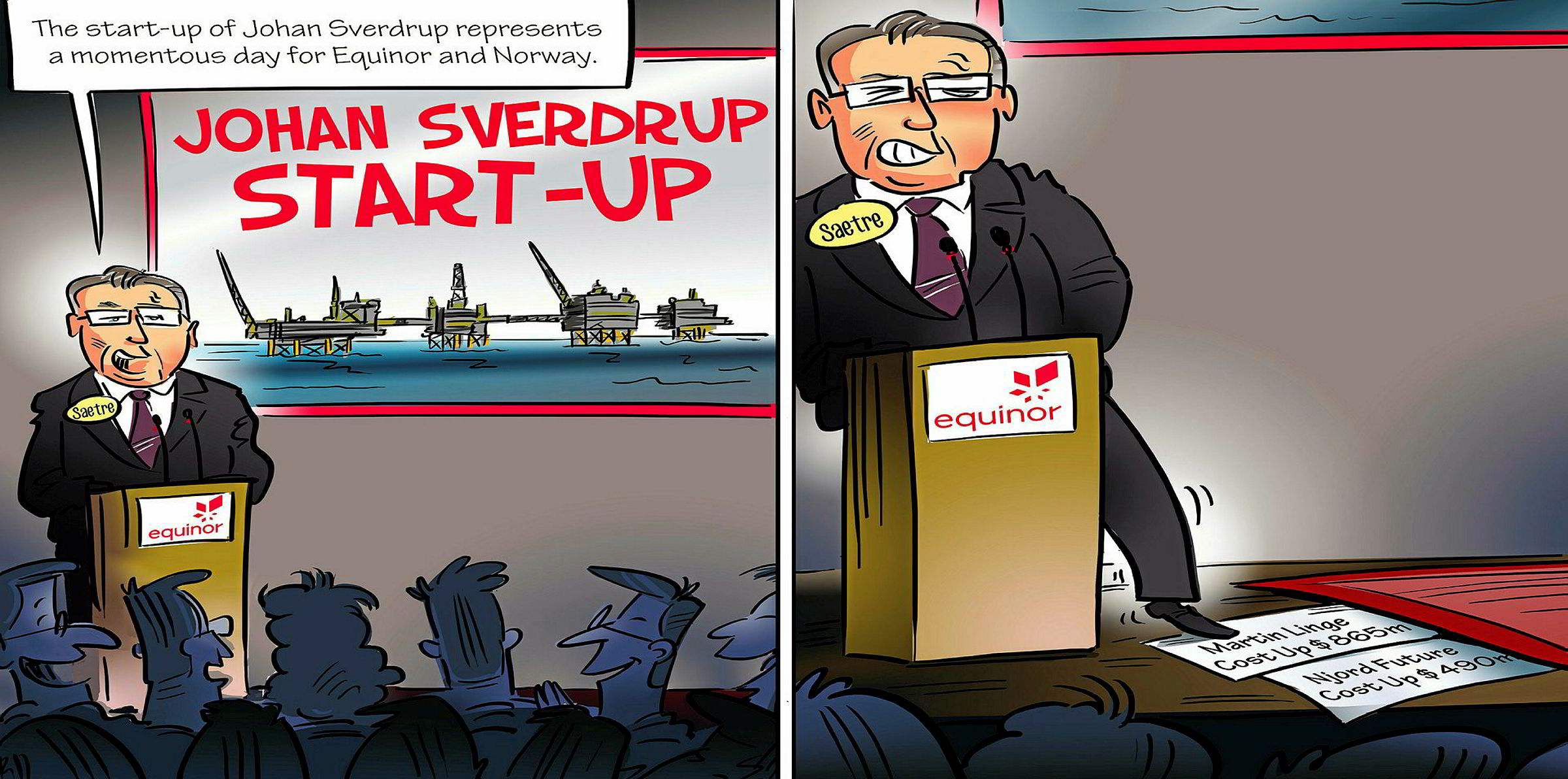

OPINION: The fanfare over the launch of production from the huge Johan Sverdrup field off Norway has been muted as concerns over the consequences for the climate have put a dampener on the oil party.

Start-up of the North Sea field — the biggest to be developed in three decades off the country — has come amid growing pressure from the environmental lobby to dismantle the key oil and gas sector as part of a global effort to alleviate climate change.

Johan Sverdrup is expected ultimately to contribute around one-third of Norway’s crude output and is set to produce for 50 years — well beyond a proposed European Union target to achieve net-zero carbon dioxide emissions by 2050.

The apparent paradox of beefing up the country’s oil output from the 2.7 billion-barrel field and curbing greenhouse gas emissions has not been lost on operator Equinor.

It has trumpeted the fact that Johan Sverdrup will generate a “world-beating” low 0.67kg of CO2 per barrel produced as the field is powered from shore using electricity mainly generated by hydropower, compared with an average off Norway of 8kg per barrel and a global average of 18kg. However, this cannot mask the fact that, if all of the field’s oil is burned, it will produce more than 1.1 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide — more than 20 times Norway’s annual emissions.

The Norwegian government already admits the country will be unable to meet its emissions target of 48.6 million tonnes for 2020, having also committed to reach a goal of 45 million tonnes by 2030. The regime is also under fire from political opponents for failing to allocate sufficient funds to meet climate goals in its proposed budget for next year.

However, green calls to eradicate the country’s oil and gas industry fail to take into account the vital revenue required from the sector to invest in technologies for the energy transition, as well as global market realities given renewables will be insufficient to meet an expected surge in future energy demand.

So, rather than a blot on the climate landscape, Johan Sverdrup could also be seen as the low-carbon model for the oilfield of the future.

(This is an Upstream opinion article.)